[?] Subscribe To This Site

Photo Copyright

|

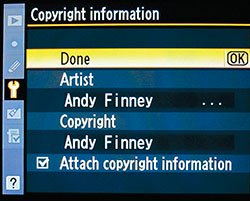

| Your camera might even allow you to include your name, as creator, in its metadata. Ideally, every digital camera should allow you to 'sign' your work in this way. I'll come onto the legal reasons why this is important in a moment, but for now here's a suggestion to camera makers: it's not just owners of DSLRs who deserve a credit. |  |

| Your camera may allow you to include your name, as creator, in its metadata. Here's the screen from my Nikon D300 where I can do this. |

The metadata in an image should remain with it, so that it remains accessible when it is posted on the web. It's surprising how few web images have any useful metadata in them. In many cases, the people uploading them don't realise that they can include metadata, and there are even some image processing applications that strip it all out.

photo copyright

Some publishers routinely strip out metadata (which may be illegal) and don't always replace it with a visible credit. This may be by accident, because of the way their content management systems work, or it may be deliberate, motivated by a concern that the metadata might contain something contentious.

It also seems that some photo editing software does not update the thumbnail metadata image when a photo is cropped, which has the potential to be embarrassing. There is another risk, which is more applicable to things like spreadsheets and documents than to images, which is that metadata left over from a previous version, or even a completely different document, can sometimes be left in the file.

photo copyright

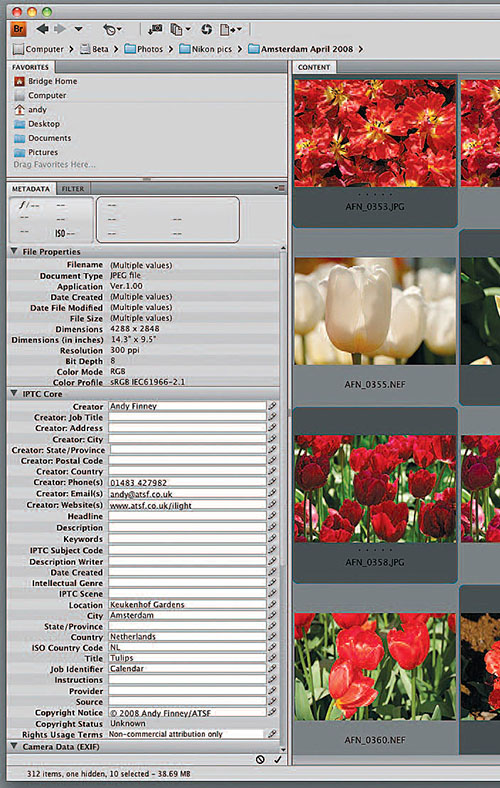

There are numerous applications that can edit metadata in photographs, some dedicated to that task, and in most cases you can do this to a batch of images as well as individual ones. This is how you can add location names to photographs, or identify the job they may be associated with. You shouldn't be able to edit the camera data, and why would you?

photo copyright

It is also a way to add copyright information, if you camera hasn't already done it. In the screen shot of Adobe Bridge CS4 tackling the metadata on some photo-graphs of Dutch tulips, above, you can see the list of possible metadata items down the left hand side, and this is not the whole list.

You don't have to fill in every item, just the ones that you think are important and/or appropriate. Note that only the Jpeg versions of the images were selected in this case.

|

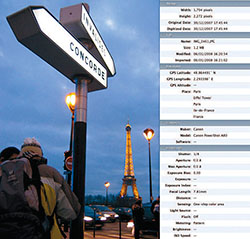

The

metadata options may be simpler in other

programs such as the ‘extended info’ (metadata) in Apple's

iPhoto. If your camera doesn’t include GPS, then this program allows

you to pinpoint the location, in this case Paris, on a map after the

event. Since photographic metadata can include a thumbnail image, the data doesn’t have to be text (although for technical reasons, images may be converted into an encoded text format). |

| Extended info’ (metadata) in Apple's iPhoto. |

Metadata provides you with a way of labelling your digital photographs that, because it's usually part of the image file, sticks with them unless the data is deliberately or accidentally removed.

|

METADATA

|

Moral rights

photo copyright

You have a legal right to be credited for the use of your photograph, and this is known as the moral right of attribution. Moral rights were introduced into UK law in the 1988 copyright act, although they were well established in some other legal systems prior to that, notably the French, where they are known as droit d'auteur.

The two key moral rights are those of paternity (or attribution) and integrity. Integrity gives the creator a right to control changes to their work. In the UK, you need to assert your right to be credited as the creator (a bone of contention with many creators).

Your moral rights are separate from any copyright you may have in your photograph and, unlike a copyright, cannot be assigned or licensed to anyone else. You can only waive them, and many licence agreements include a waiver of moral rights

It is undoubtedly right and proper to credit a photograph when it's used in a publication (whether on paper or on a website) although the law excludes an automatic right in two cases that many photographers would find controversial: reporting of current events and in newspapers, magazines and 'similar periodicals'. Even so, a right to be credited can be agreed, such as in a contract. Arguably, since electronic publication allows more space for lists of contributors, crediting should be more widespread in the digital arena.

photo copyright

Any creator has a moral right to be credited if they wish, but there are other reasons why credits are useful. You will often see that not only the photographer is credited, but also their agency. In some instances, only the agency or library will be credited. This provides other potential users of the image with a contact point so they too can licence it.

Public domain

photo copyright

Some people think that putting a photograph online, whether on your own website or using a photo service such as Flickr, puts the photograph into the public domain, and means that copyright does not apply. This is not the case.

Since you don’t have to claim your copyright, just putting your photo online in no way affects its copyright. You obviously intend that people will look at it, so there is what is called an implied licence for people accessing your photo on their computer so that they can display it on their screen (which is in fact a copying of the image) and, perhaps, print it out or take a copy for their own private purposes, because they like it.

photo copyright

However, putting an image on your website does not imply anything else. If you want to be more specific, then you can put explicit licence terms on or with the image, and Flickr allows you to choose what level of rights you might want to apply, such as 'All rights reserved', or choosing one of the Creative Commons licences, which allow options such as 'non-commercial use with attribution'.

Since people who like photographs continue to point to them in their blogs, and take them out of the context of your web page, you might want to consider putting a visible credit in the image itself, and you should also consider carefully the resolution/image size of photographs you put online.

Watermarks

photo copyright

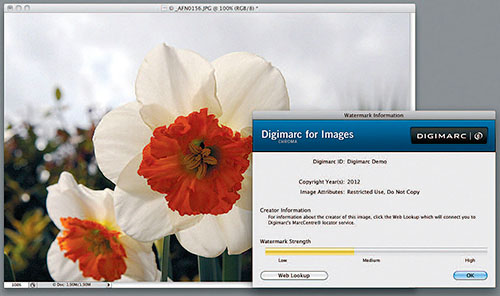

Of course, adding a visible credit is one form of watermarking, which is widespread not only in photographs on the web but even in the corner of most television services. Watermarking can be invisible, or effectively so, and there are several solutions available with which you can add such a watermark and even track it. One of these, Digimarc, comes bundled in its basic form with Photoshop.

Above is a screen grab of Digimarc in action, with a photograph where I applied a full strength 'invisible' watermark, and then shrank the image size to about 1/16 (area) of the original.

The watermark was still there as you can see, showing as reduced to medium strength but still readable. It contains some metadata, in this case a copyright year and an image attribute, but it doesn't identify me, because this is the free version.

photo copyright

The effect of the full watermark was just about visible on the original image as a slight amount of 'grain' but was not in any way disturbing, and if I wasn't looking for it I probably wouldn't have noticed it. However, adding the watermark may increase the size of a compressed file.

Digimarc provides a service where, for paid up and registered users, it searches the web looking for images, so that you can track your images and see if anyone is publishing them who shouldn't be.

photo copyright

This kind of watermarking doesn't have to be done with a Jpeg image; it can be applied to any form of compression, and even an uncompressed image. The key thing is that it is hidden among the fine detail, and we don't usually see any evidence of it.

There is a trade-off between visibility and ruggedness, and by ruggedness I mean the ability of the watermark to withstand image processing, and be detectable even on a resized, cropped or printed copy.

photo copyright

This technique can be used on any digital file, compressed or not, photographic image or not. Inaudible information can be used to watermark sound files for instance, and broadcasters often add invisible watermarks to their transmissions so they can identify copies.

photo copyright

This raises an important point, since if you want to prove that someone has pirated your creation, you first have to prove that it is yours, and watermarking is promoted as being a useful aid to that process.

Electronic recognition

photo copyright

It should be possible to electronically recognise images on the web by using the image itself, rather than any watermark. Image recognition is still extremely difficult and unreliable, although for specific cases, such as recognising the location of a face in an image, it works well enough to be included in consumer cameras.

As to a general way of checking whether a resized and processed version of your photo has been used on another website, I fear we are still some way off.

Conclusion

photo copyright

Remember that it is your legal (moral) right to be credited for your work as a photographer. You should make use of metadata in any image you distribute or publish to claim and preserve that right, and you might consider visible or invisible watermarking.

We all know that 'other things' can sometimes get in the way of any best practice, so making as much use of automatic aids as you can will help, starting with seeing if you can enter your 'creator' information into your camera.

"Article first published in the RPS Journal February 2012 - No reproduction without permission."

Andy Finney is The Royal Photographic Society’s representative on the British Copyright Council and can be contacted at his website - http://www.atsf.co.uk.

|

Return from Photo Copyright to Better Photographs Home Page.

|

| Image of the Month |

|

| Click here to download it. |

| Find It |

Custom Search

|

| All of the advice, tutorials, masterclasses and ideas on this website are available to you at no charge. Even so, its upkeep does incur costs. |

|

| If you feel that

the site has helped you then any contribution you make, however small,

would go towards its ongoing maintenance and development. Thanks for your help. |

| Book of the Month |

|

| Click here to read the review. |

|

|

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.